Basquiat Soundtracks sheds light on the intense relationship between Basquiat’s artistic practice and music, surpassing largely the mere fact that he painted with music in the background. Reflecting Basquiat’s deep interest in the legacy of the African diaspora and his acute awareness of the politics of race in the United States, the exhibition presents a captivating display of nearly one hundred works, rare archives, emblematic musical instruments, previously unpublished audio-visual document, and a carefully curated collection 104 musical songs that were closely related to Basquiat. Visitors can also download the songs as a playlist using a QR code.

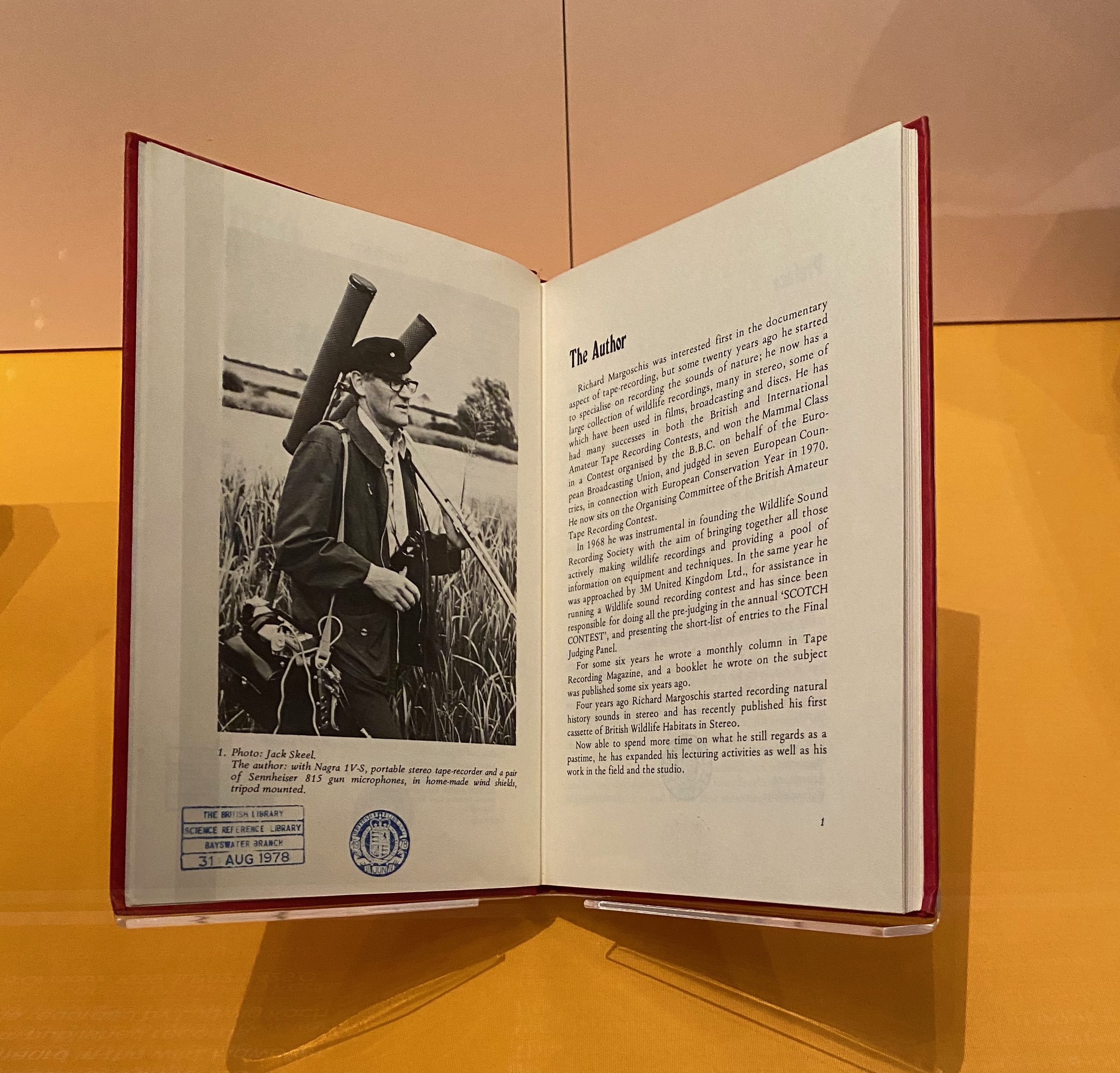

In relation to music, visitors are told about Basquiat’s involvement in the Manhattan music scene, his unofficial role as the leader of the band Gray, named after Gray’s Anatomy (1858) the medical book that had a profound influence on Basquiat, as well as his profound relationship with new urban sound like no wave and hip hop, rap, jazz and experience as a record producer. A music lover, Basquiat moreover collected over 3.000 records, ranging in genre from classical to blues and jazz, zyeco, soul, reggae, hip-hop, opera and rock.

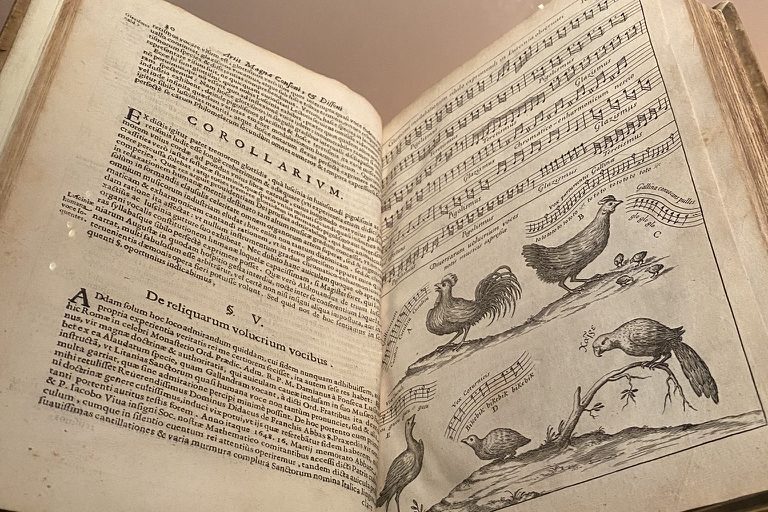

The exhibition stands out for its innovative approach in highlighting how Basquiat transformed the audible into the visible. In reveals how his paintings abound are rich with elements that render noise visible, namely by using onomatopoeia and crisscrossing vehicles, cartoon quotes and anatomical drawings that present the body and organs as emitters of sounds.

In terms of museum practice, there is a noticeable endeavour to place equal emphasis on hearing as well as seeing, aligning with the latest trends in sensory museology. Together with exhibiting Basquiat’s works as part of a bold scenography, the exhibition features a cutting-edge audio component that attests to Basquiat’s broad and diverse musical culture. The exhibition’s soundtrack consists of almost a hundred pieces of music, artfully curated by using Bronze, a pioneering technology. Through meaningful and unpredictable associations, this technology composes a playlist that aligns with the exhibition’s themes and stages. The outcome is a generative and ever-evolving soundtrack, providing visitors with a unique and multifaceted listening experience inspired by Basquiat’s own musical influences.

As I conclude writing this post, I closed all the photos and reviews, turning inward to reflect on my personal experience with the exhibition. I aimed to grasp the lingering feelings and ideas about Basquiat that stayed with me. What emerges vividly is Basquiat’s universal dimension and its sensibility, which can be described as simultaneously polemic and poetic, conflicting yet tender. Although it might seem like a straightforward endeavour, achieving this level of complexity in an exhibition is undoubtedly a challenging standard to meet.

Unmissable!

Until 30th July 2023.